Mount Everest may be the highest point in the world, but Nanga Parbat, conquered just 36 days later, ninth on the list of highest peaks, is known as one of the most treacherous climbs in the world with a death toll of 31 at the time it was finally ascended for the first time. On July 3, 1953, after a Herculean 18-hour climb, its conqueror Hermann Buhl survived a solitary night just below its summit, staying alive by swallowing stimulant pills to keep awake.

Mount Everest may be the highest point in the world, but Nanga Parbat, conquered just 36 days later, ninth on the list of highest peaks, is known as one of the most treacherous climbs in the world with a death toll of 31 at the time it was finally ascended for the first time. On July 3, 1953, after a Herculean 18-hour climb, its conqueror Hermann Buhl survived a solitary night just below its summit, staying alive by swallowing stimulant pills to keep awake.It was Buhl's extraordinary physical and mental stamina -- developed from an early age by death-defying trips in the Alps, then in the Himalayas -- that let him survive to tell his tale.

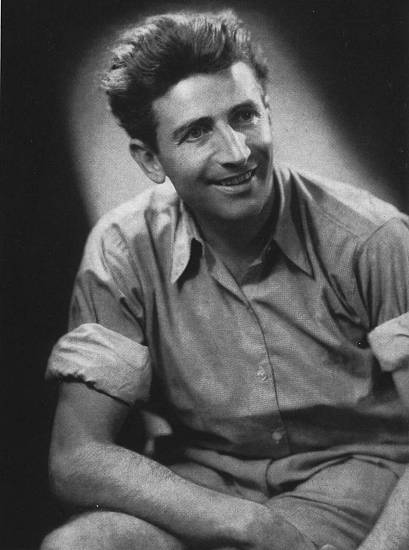

Hermann Buhl was born on September 21, 1924 in Innsbruck/Tyrol as youngest of four children to poor parents. After the death of his mother he spent his first years in an orphanage. In the Thirties, the boy, who was considered sickly and over-sensitive, went on his first mountaineering tours in the Tuxer Alpen and the Karwendel. 1939, he joined the Innsbruck section of the DAV and soon improved his skills and performance. Soon he mastered the most diffcult climbing routes up to grade VI.

After leaving school, Hermann Buhl was apprenticed to become a forwarding merchant. In 1943, he joined the army and spent the war as mountain infanteryman in Italy, where he took part in the Battle of Monte Cassino. After release from American war captivity, he returned to his native Innsbruck and took on odd jobs. In the late Fourties, he trained to become a mountain guide. During the following years he mastered, in spite of almost nonexisting funds, spectacular ascents, some of them first ascents, in the Alps.

In March 1951, Hermann Buhl married Eugenie Högerle from Ramsau near Berchtesgaden in Bavaria and became father of three daughters. The fact that the renowned sports goods retailer Sporthaus Schuster in Munich employed him as a salesman and advisor for mountaineering goods helped him out of his difficult financial situation.

In 1953, Nanga Parbat, the mountain in Northern Pakistan that had already cost so many lives, became again subject to German and Austrian interest. Even Mount Everest, the world's highest mountain, had been ascended before this ice-covered and avalanche-prone giant.

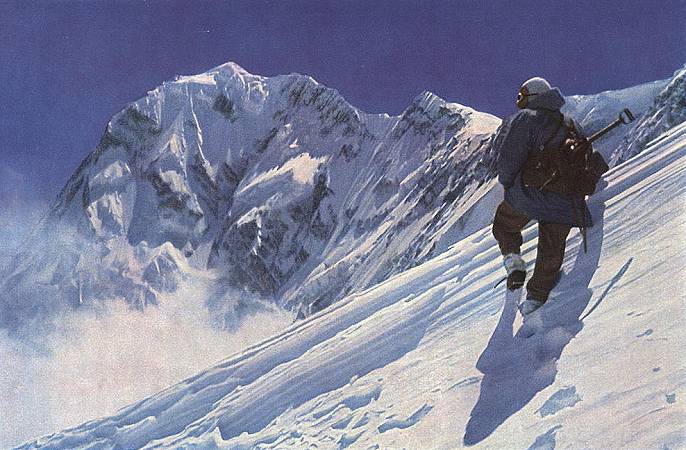

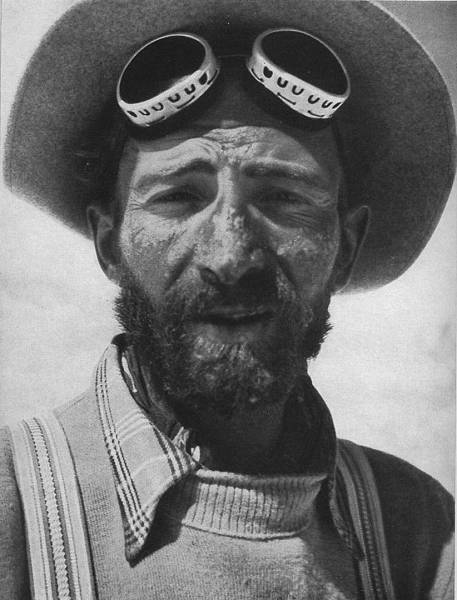

Hermann Buhl ascending the eastern ridge of the Nanga Parbat.

Hermann Buhl ascending the eastern ridge of the Nanga Parbat.The initiator for the 1953 German-Austrian Himalaya expedition was Dr. Karl Herrligkoffer, whose organisation and preparation hadn't won the trust of the major alpine organisations, so he had difficulties hiring renowned mountaineers. Eventually he found a couple of climbers with high altitude experience in the Himalayas: Aschenbrenner (a veteran from an ill-fated expedition in 1934) and Frauenberger. Last but not least he managed to engage a famous duo from the Alps, Hermann Buhl and Kuno Rainer.

A base camp was established during the end of May. Camp I - IV were consecutively put up and supplies and equipment were taken up there. Heavy snowfall and uncertain weather rendered all attempts at reaching greater heights impossible. On June 30, Herrligkoffer ordered everyone back to base camp.

Suddenly, on July 1, the weather changed. Buhl, Kampter, Frauenberger and the cameraman Ertl were still in the higher camps. They had refused to retreat after a discussion via radio and had managed to get their way. On July 2, Buhl and Kempter established Camp V at the col on the ridge below the Silver Saddle at 6,900 meters. Ertl and Frauenberger returned to Camp IV. The weather seemed to be stable. Buhls plan was to reach the Silver Saddle at 7,450 meters and then the big plateau above. From there he could either ascend the preliminary summit or the Northern Summit.

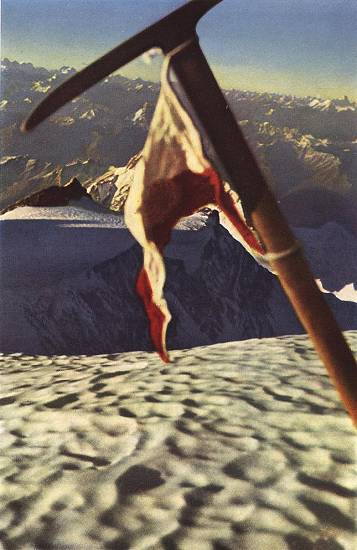

Picture taken by Hermann Buhl on the summit of the Nanga Parbat. In 1999, the ice-axe was retrieved by the Japanese mountaineer Takehido Ikeda and given to Eugenie Buhl.

Picture taken by Hermann Buhl on the summit of the Nanga Parbat. In 1999, the ice-axe was retrieved by the Japanese mountaineer Takehido Ikeda and given to Eugenie Buhl. At 01.00h on July 3, Buhl left Camp V heading upwards, Kempter had difficulties leaving his sleeping bag and followed one hour later. The snow conditions were good and the night was clear with the moon lighting up the mountain. At 05:00h, when Buhl reached the Silver Saddle, the sun rose. The plateau spanning three kilometer taxed Buhl's strength. The heat was almost overwhelming and the air stood completely still. At the end of the plateau, Buhl had some tea and left his pack behind, which enabled him to move more easily. Kempter had reached the plateau as well in the meantime, but Buhl was moving too fast and was way ahead. Realising he would never catch up, Kempter turned back and reached Camp V safely.

Buhl reached the col below the summit (7,800 meters) at 14:00h. He still had the technically most difficult part of the whole climb ahead of him and the last 300 meters didn't look inviting. After an inner struggle, he decided to continue. He took a dose of Pervitin (a stimulant) and went on. At 18:00h Buhl reached the shoulder and one hour later the summit. It was dead calm and perfectly clear.

The chapter Nanga Parbat was closed for the lonely man on the summit.

Down below, Kempter had reported that Buhl had continued alone towards the summit, and from each camp the men looked up to the Silver Saddle hoping to see Buhl on his way back. But nothing was to be seen. Frauenberger had returned to Camp V during the day and spent the night there together with Kempter. They could, however, not sleep, thinking what might have happened to their companion.

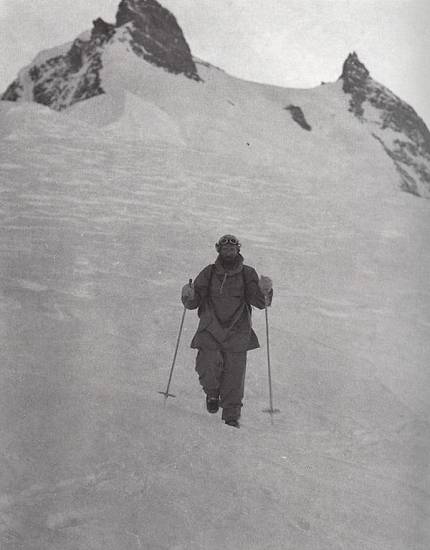

Hermann Buhl returning from his solo ascent to the Nanga Parbat to camp V on July 4, 1953 at 19:00h, 41 hours after he took off. The Siver Saddle in the background.

Hermann Buhl returning from his solo ascent to the Nanga Parbat to camp V on July 4, 1953 at 19:00h, 41 hours after he took off. The Siver Saddle in the background.While Buhl was still at the summit, the sun went down. He drank his last tea and planted his ice-axe with the Pakistani and the Tyrolean flag there and took a few pictures. Night was falling fast as he started his descent.

Above 8,000 metres, at a tiny ledge below the shoulder, he was forced to emergency bivouac -- without a sleeping bag or warm clothes because he had left his pack at the plateau. Standing on a piece of rock between 21:00h and 04:00h, he spent the night up in Nanga Parbat's "death-zone". The wind was calm and the night clear and he was loosing all the feeling in his feet. At dawn, he continued to descend. He eventually reached the plateau and found his pack, but was in no condition to eat or drink anything. Haunted by hallucinations he struggled on downwards across the plateau in the burning sun. His thirst became overwhelming, some more Pervitin mobilised his last strength and at 17:30h Buhl reached the Silver Saddle.

The most famous picture of Herman Buhl and probably the most famous picture in mountaineering history. It was taken by Fritz Aumann on July 5, 1953, between camp III and II.

The most famous picture of Herman Buhl and probably the most famous picture in mountaineering history. It was taken by Fritz Aumann on July 5, 1953, between camp III and II.At the time this picture was taken, Herman Buhl is 29.

Meanwhile, while the men at camp V where making plans to go and find out what had happened to their companion the next day, they suddenly saw a small dot on the Silver Saddle moving downwards. It was Hermann Buhl! His happiness at being reunited with his friends was indescribable.

Buhl was lucky to return from the Nanga Parbat with just a few frostbitten toes, lucky to return at all. If anyone at this time could manage such an ordeal and survive -- it was Hermann Buhl. Also, he was possibly the first mountaineer to apply 'Alpine Style' climbing techniques to the great peaks in the Himalaya.

Four years later on Broad Peak, Hemann Buhl and his companions proved that, without any help from native porters, a small team could climb an 8,000 metre peak. But it was Buhl's last summit. Some days later, attempting Chogolisa together with Kurt Diemberger, he fell through a cornice to his death. His body was never found.

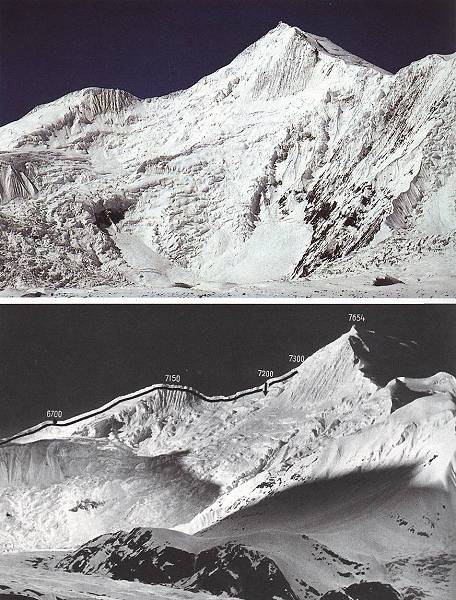

Four years later on Broad Peak, Hemann Buhl and his companions proved that, without any help from native porters, a small team could climb an 8,000 metre peak. But it was Buhl's last summit. Some days later, attempting Chogolisa together with Kurt Diemberger, he fell through a cornice to his death. His body was never found.Top picture:

The Chogolisa North Face, 7654 m, today

Picture below:

The Chogolisa North Face 1957

The arrow at 7200 m marks the point where Hermann Buhl fell to his death.

"Mountaineering is a relentless pursuit. One climbs further and further yet never reaches the destination. Perhaps that is what gives it its own particular charm. One is constantly searching for something never to be found."

- Hermann Buhl

My main sources were Die Hermann Buhl Homepage and a mountaineering site, JERBERYD.COM.

No comments:

Post a Comment